arXiv 2023. [Paper] [Page] [Github]

Axel Sauer, Tero Karras, Samuli Laine, Andreas Geiger, Timo Aila

University of Tubingen, Tubingen AI Center | NVIDIA

23 Jan 2023

Introduction

In text-to-image synthesis, a new image is created based on a text prompt. The state-of-the-art of this task has recently taken a dramatic leap thanks to two key ideas.

- Using large pre-trained language models as encoders for prompts, we can condition synthesis based on general language understanding.

- With large training data consisting of hundreds of millions of image-caption pairs, the model can synthesize almost anything you can imagine.

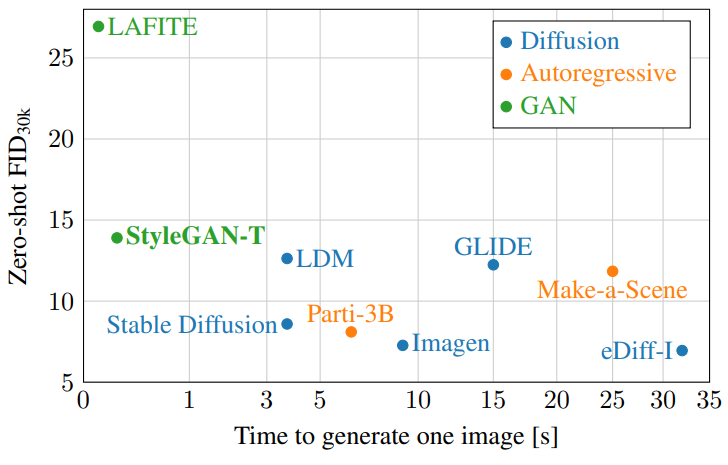

Training datasets continue to grow rapidly in size and coverage. As a result, the text-to-image model must be scalable to large volumes capable of absorbing training data. Recent success in large-scale text-to-image generation has been driven by the diffusion model (DM) and autoregressive model (ARM), which seem to have these properties built-in, and have the ability to handle highly multi-modal data.

Interestingly, GANs, the dominant family of generative models in smaller and less diverse datasets, have not been particularly successful in this task. The goal of this paper is to show that GANs can regain their competitiveness.

The main advantages provided by GANs are the speed of inference and the control of synthetic results through latent space manipulation. In particular, StyleGAN has a thoroughly researched latent space, so the generated image can be controlled in principle. Although there has been noticeable progress in speeding up DM, it is still far behind GANs that require only a single forward pass.

GANs similarly lag behind diffusion models in ImageNet synthesis until the discriminator architecture is redesigned, GANs may close the gap. Motivate you to be able to Starting with StyleGAN-XL, we revisit generator and discriminator architectures, taking into account the specific requirements of large-scale text-to-image tasks: large, highly diverse datasets, robust text matching, and the trade-off between text matching and controllable transformations. see.

The authors note that due to the constraints of the GPUs available to train the final model at scale (NVIDIA A100 64 x 4 weeks), this is likely not sufficient for state-of-the-art high-resolution results, so we had to prioritize it. do. Although the ability of GANs to scale to high resolution is well known, successful scaling to large-scale text-to-image tasks has not yet been studied. Therefore, the authors mainly focus on solving this task at low resolution with a limited budget for the super-resolution step.

StyleGAN-XL

The architectural design of this paper is based on StyleGAN-XL, similar to the original StyleGAN, first normally distributed input latent code $ by mapping network Process z$ to generate intermediate latent coder $w$. This intermediate latent is used to modulate the convolutional layer in the synthetic network using the weight demodulation technique introduced in StyleGAN2. The synthesis network of StyleGAN-XL uses the alias-free primitive operation of StyleGAN3 to achieve translational equivariance. That is, it ensures that the synthetic network has no preferred location for the generated features.

StyleGAN-XL has a unique discriminator design in which multiple discriminator heads operate on the feature projections of two fixed, pre-trained feature extraction networks (DeiT-M and EfficientNet). The output of the feature extraction networks is fed through a randomized cross-channel and cross-scale mixing module. As a result, 2 feature pyramids with 4 resolution levels each are generated and processed in 8 discriminator heads. Additional pre-trained clasifier networks are used to provide guidance during learning.

The synthesis network of StyleGAN-XL is trained incrementally, increasing the output resolution over time by introducing new synthesis layers if the current resolution does not improve. Unlike previous incremental growth approaches, the discriminator structure does not change during training. Instead, the initial low-resolution image is upsampled as needed to fit the discriminator. Also, already learned composite layers are fixed when additional layers are added.

For class conditional synthesis, StyleGAN-XL embeds one-hot class labels into $z$ and uses a projection discriminator.

StyleGAN-T

1. Redesigning the Generator

StyleGAN-XL uses the StyleGAN3 layer to achieve translational equivariance. Equivariance can be desirable for a variety of applications, but will not be necessary for text-to-image synthesis, as none of the successful DM/ARM-based methods are equivariance. Additionally, equivariance constraints add computational cost and impose certain restrictions on the training data that large image datasets typically violate.

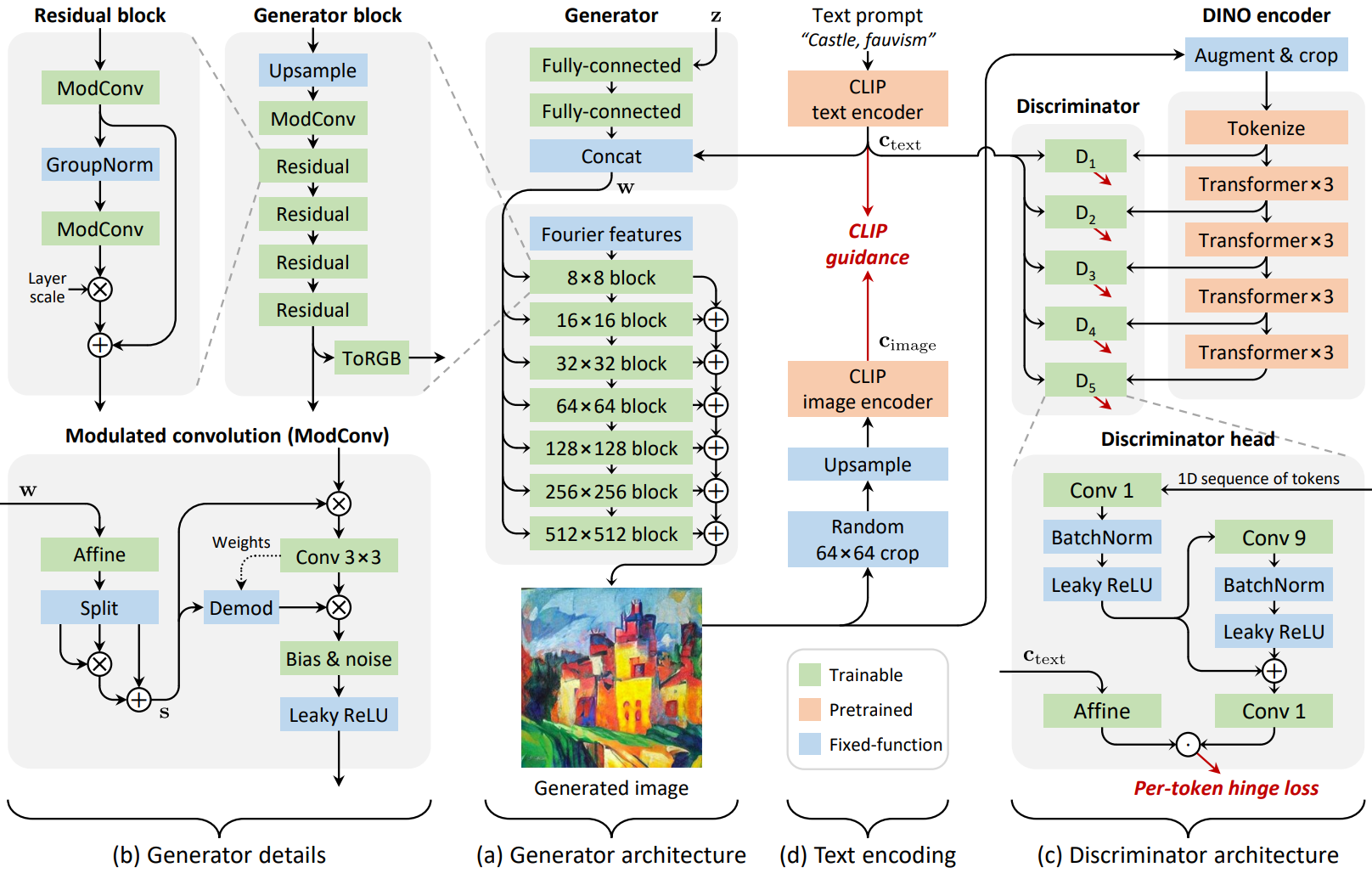

For this reason, we discard equivariance and switch to the StyleGAN2 backbone for the synthesis layer, including output skip connections and spatial noise inputs that facilitate stochastic changes in low-level detail. After these changes, the generator’s high-level architecture is shown in (a) of the figure above. Two further changes to the details of the generator architecture are proposed ((b) in the figure above).

Residual convolutions

Since we aim to significantly increase model capacity, generators must be scalable in both width and depth. However, in the default configuration, when the depth of the generator increases significantly, initial mode collapse occurs in training. An important component of a modern CNN architecture is an easily optimizable residual block that normalizes the input and expands the output. The authors make half of the convolution layer residual and wrap it with GroupNorm for normalization and Layer Scale for scaling the contribution. A layer scale with a low initial value of $10^{-5}$ gradually reduces the contribution of the convolution layer, significantly stabilizing the initial training iteration. This design allows for a significant increase in the total number of layers, by about 2.3x in the lightweight configuration and 4.5x in the final model. Match the number of parameters of the StyleGAN-XL baseline for fair comparison.

Stronger conditioning

Text-to-image settings are tricky because the transformation factors can vary greatly from prompt to prompt. The prompt “face close-up” should generate faces with different eye colors, skin tones, and proportions, while the prompt “beautiful scenery” should generate scenes of different regions, seasons, and days. In a style-driven architecture, all these transformations must be implemented by per-layer styles. So text conditioning needs to affect styles much more strongly than is necessary for a simple setup.

In initial testing, the authors observed a clear tendency for the input latent $z$ to dominate the text embedding $c_\textrm{text}$ in the baseline architecture, leading to poor text matching. To address this, we are introducing two changes aimed at amplifying the role of $c_\textrm{text}$. First, we make the text embedding bypass the mapping network according to the observation of Disentangling Random and Cyclic Effects in Time-Lapse Sequences paper. A similar design is also used in LAFITE and assumes that the CLIP text encoder defines an appropriate intermediate latent space for text conditioning. Therefore, $c_\textrm{text}$ is directly connected to $w$, and a set of affine transforms are used to generate style $\tilde{s}$ for each layer.

Second, instead of using the result $\tilde{s}$ to modulate the convolution verbatim, we split it into three vectors of the same dimension $\tilde{s}_{1,2,3}$ and the final style vector is Calculate.

\[\begin{equation} s = \tilde{s}_1 \odot \tilde{s}_2 + \tilde{s}_3 \end{equation}\]The key to this operation is element-wise multiplication, which effectively converts the affine transform into a second-order polynomial network, increasing expressive power. The stacked MLP-based conditioning layer of DF-GAN implicitly contains similar quadratic terms.

2. Redesigning the Discriminator

This paper redesigns the discriminator from scratch, but maintains the core idea of StyleGAN-XL that it relies on a fixed, pre-trained feature network and uses multiple discriminator heads.

Feature networks

For the feature network, we choose ViT-S trained as a self-supervised DINO objective. The network is lightweight, fast to evaluate, and encodes semantic information at high spatial resolution. An added benefit of using self-supervised feature networks is avoiding the fear of potentially compromising the FID.

Architecture

The discriminator architecture is shown in (c) of the figure above. ViT is isotropic. That is, the representation size (token$\times$ channel) and receptive field are the same throughout the network. This isotropy allows us to use the same architecture for all discriminator heads and evenly space them between the Transformer layers. Multiple heads are known to be beneficial, and the authors used five heads in their design.

The discriminator head is minimal as detailed at the bottom of (c) in the figure above. The kernel width of the residual convolution controls the receptive field of the head in the token sequence. The authors found that the 1D convolution applied to the token sequence performs as well as the 2D convolution applied to the spatially reconstructed token, indicating that the discrimination task does not benefit from the remaining 2D structure of the token. We evaluate the hinge loss independently for each token in every head.

ProjectedGAN provides batch statistics to the discriminator using synchronous BatchNorm. BatchNorm is problematic when scaling to a multi-node setup as it requires communication between the nodes and the GPU. We use a variant version that computes batch statistics for small virtual batches. Batch statistics are not synchronized across devices, but are calculated per mini-batch locally. It also does not use execution statistics, so there is no additional communication overhead between GPUs.

Augmentations

Differentiable data augmentation is applied using default parameters before the discriminator’s feature network. Use random crop when training at resolutions greater than 224$\times$224 pixels.

3. Variation vs. Text Alignment Tradeoffs

Guidance is currently an essential component of the text-to-image diffusion model. Guidance trades variation for improvement of image quality in a principled way, favoring images that strongly match text conditions. Indeed, guidance greatly improves outcomes. Thus, the authors try to approximate guidance in the context of GANs.

Guiding the generator

StyleGAN-XL uses pre-trained ImageNet classes to guide the generator to easy-to-classify images by providing additional gradients during training. This method greatly improves the results. In the context of text-to-image, “classification” involves adding captions to images. So a natural extension of this approach would be to use a CLIP image encoder instead of a clasifier. Pass the generated image through the CLIP image encoder to get the caption $c_\textrm{image}$ at each generator update along VQGAN-CLIP and squared spherical distance for normalized text containing $c_\textrm{text}$ to minimize

\[\begin{equation} \mathcal{L}_\textrm{CLIP} = \textrm{arccos}^2 (c_\textrm{image} \cdot c_\textrm{text}) \end{equation}\]This additional loss term guides the generated distribution to images with captions similar to the input text encoding $c_\textrm{text}$. Thus, the effect is similar to the guidance of the diffusion model. (d) in the figure above shows the approach of this paper.

CLIP has been used in previous work to guide pretrained generators during synthesis. In contrast, the authors use CLIP as part of a loss function during training. It should be noted that overly strong CLIP guidance during training will limit distributional variability and ultimately compromise FID as image artifacts will start to be introduced. Therefore, the weighting of \(\mathcal{L}_\textrm{CLIP}\) in the total loss needs to balance image quality, text conditioning, and distribution diversity. In this paper, the weight is set to 0.2. The authors also observed that guidance only helps up to 64$\times$64 pixel resolution. At higher resolutions, apply \(\mathcal{L}_\textrm{CLIP}\) to a random 64$\times$64 pixel crop.

Guiding the text encoder

Interestingly, previous methods using pretrained generators did not report the occurrence of image artifacts at low levels. The authors assume that a fixed generator acts as a prior to suppress artifacts.

Based on this, text matching is further improved. In the first step, the generator is trainable and the text encoder is stopped. Then we introduce a second step where the generator is stopped and instead the text encoder is learnable. Regarding generator conditioning, only text encoders are trained.

The discriminator and guidance terms still receive $c_\textrm{text}$ from the original fixed encoder. This second step allows for a very high CLIP guidance weight of 50 to block artifacts and significantly improve text matching without compromising FID. Compared to the first stage, the second stage can be much shorter. After convergence, continue with the first step.

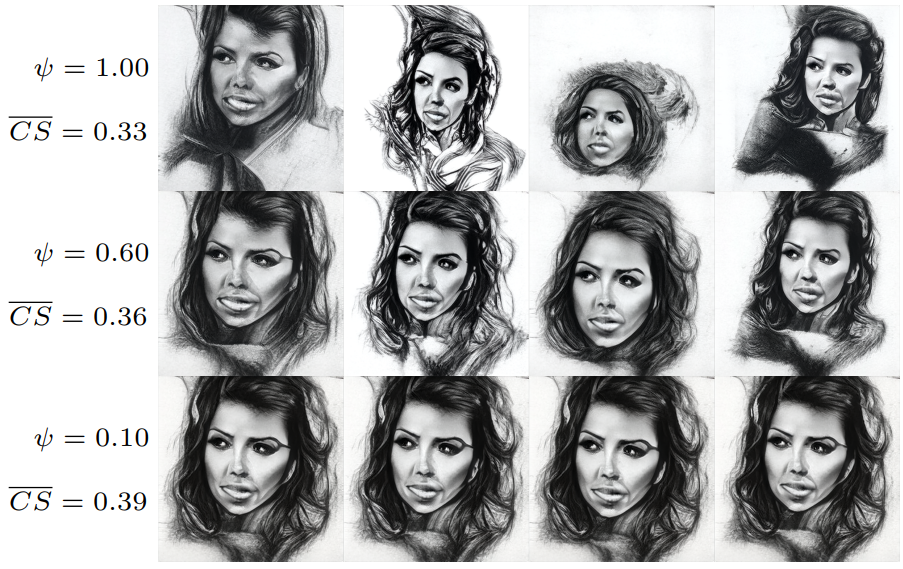

Explicit truncation

In general, variation is traded for higher fidelity in GANs using the truncation trick. Here, the sampled latent $w$ is averaged and interpolated with respect to a given conditioning input. In this way, truncation moves $w$ to dense regions where the model performs better. In the implementation, $w = [f(z), c_\textrm{text}]$, where $f(\cdot)$ represents the mapping network, so the average per prompt is \(\tilde{w} = \mathbb{ E}_z [w] = [\tilde{f}, c_\textrm{text}]\). where $\tilde{f} = \mathbb{E}_z [f(z)]$. Therefore, we implement truncation by tracking $\tilde{f}$ during training and interpolating between $\tilde{w}$ and $w$ according to the scaling parameter $\psi \in [0, 1]$ at inference time. .

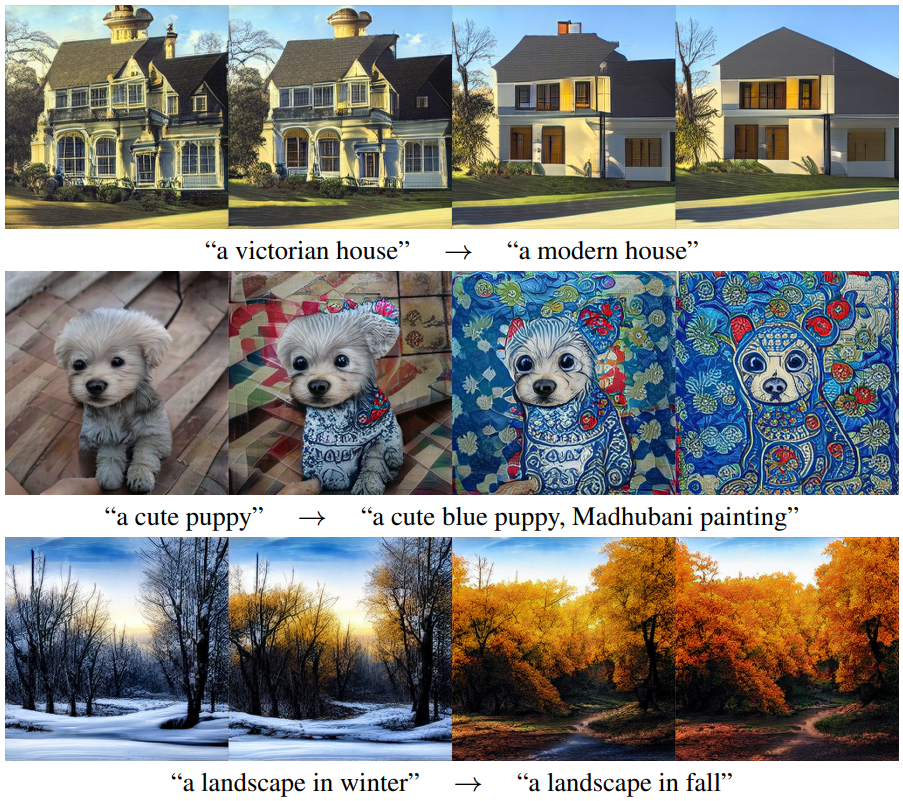

The figure above shows the effect of truncation. Indeed, this paper relies on a combination of CLIP guidance and truncation. Guidance improves the model’s full-text matching, and truncation can further improve the quality and matching of specific samples, eliminating some variation.

Experiments

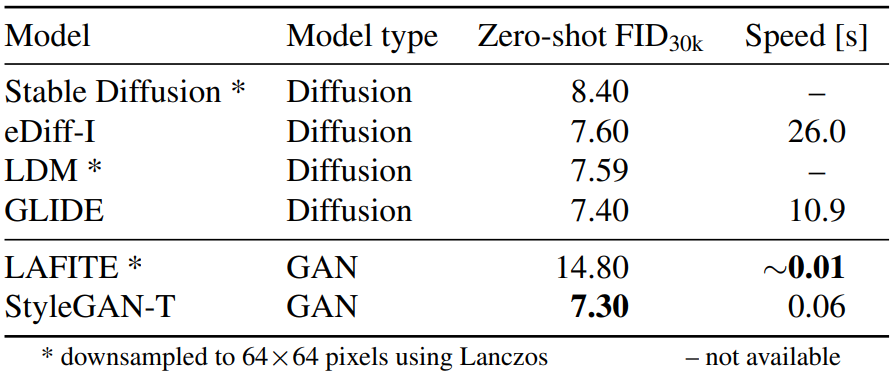

1. Quantitative Comparison to State-of-the-Art

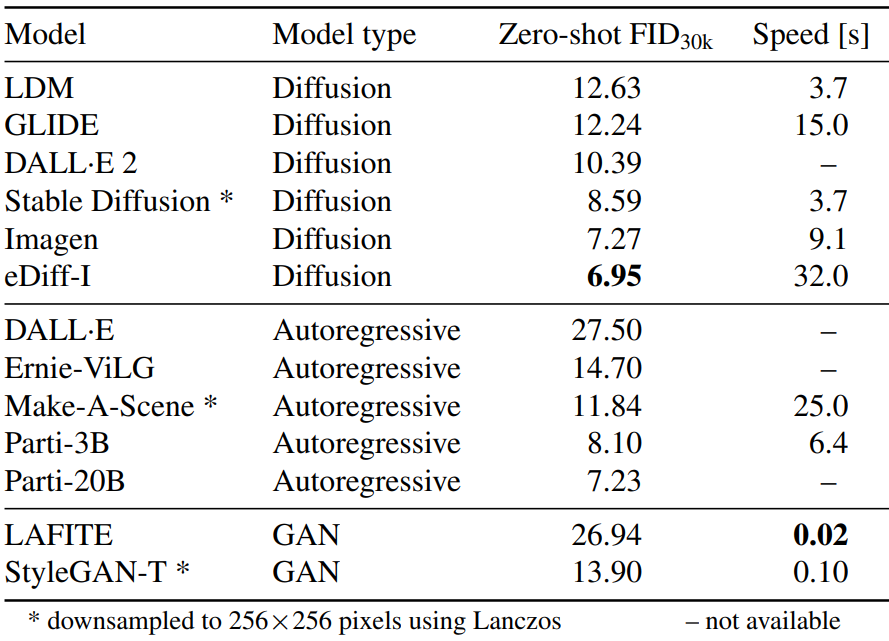

The following table compares FID at MS COCO 64$\times$64.

The following table compares FID at MS COCO 256$\times$256.

2. Evaluating Variation vs. Text Alignment

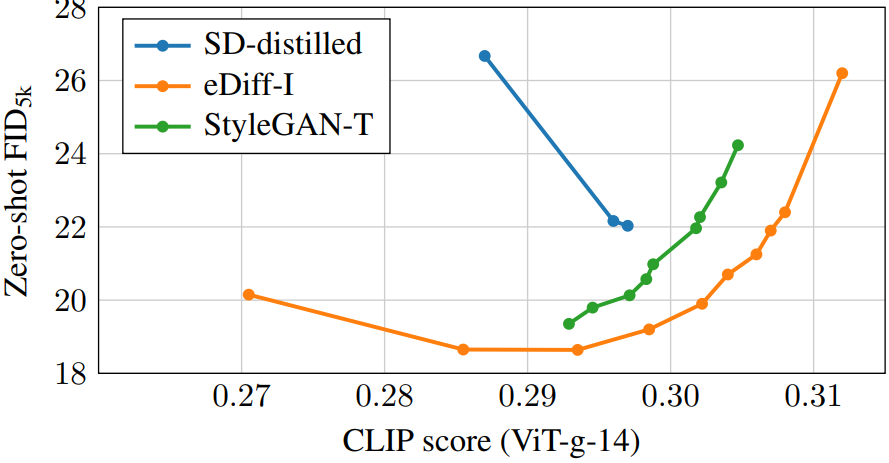

The following is a graph comparing FID and CLIP scores.

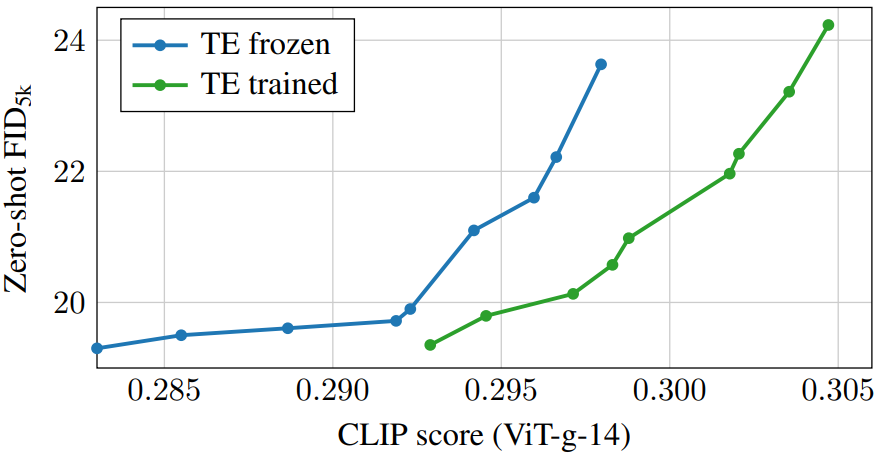

The following is the FID-CLIP score graph showing the effect of the text encoder.

You can see that training the text encoder improves overall text matching.

3. Qualitative Results

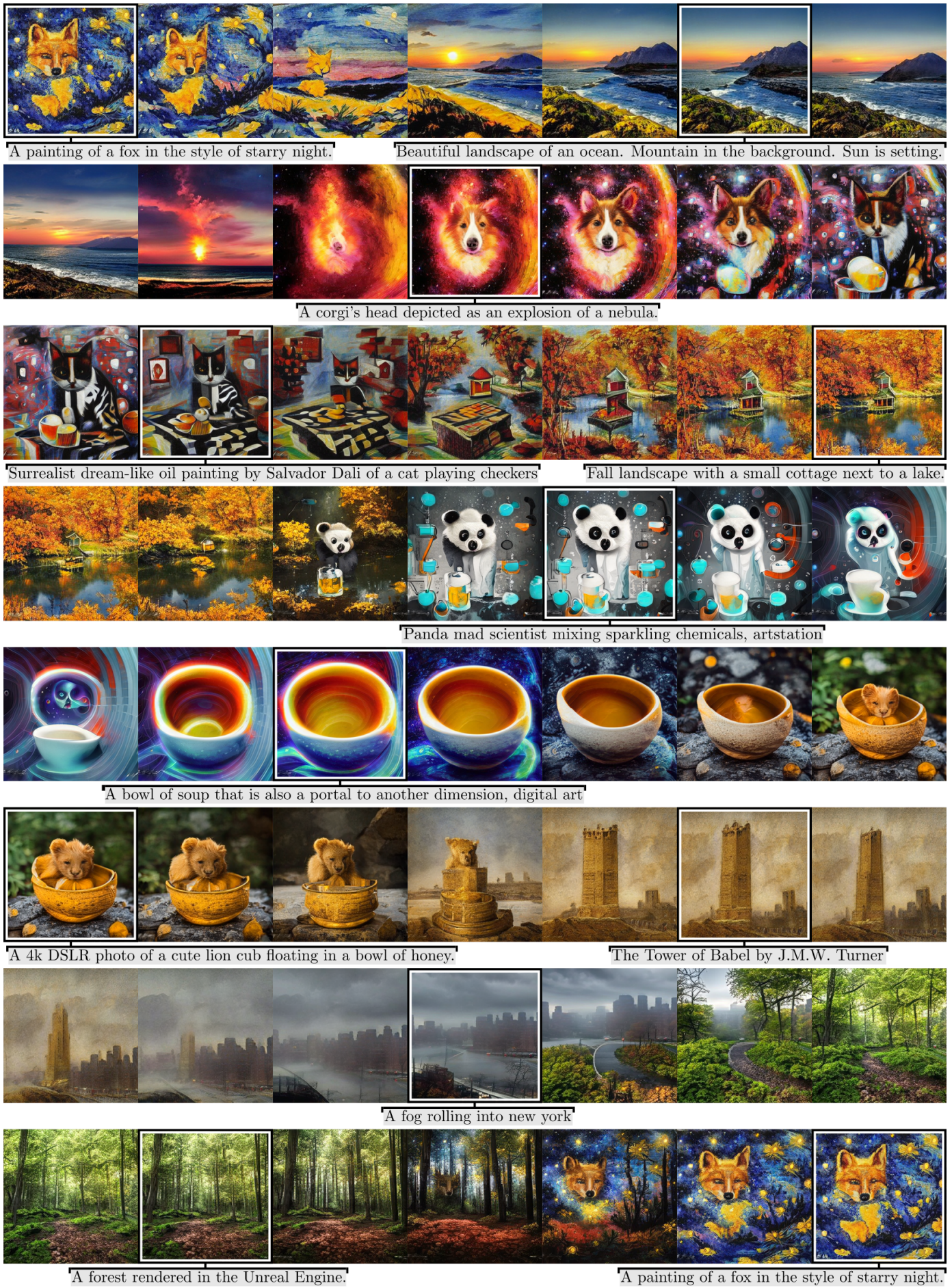

The following is a picture showing example images and their interpolation.

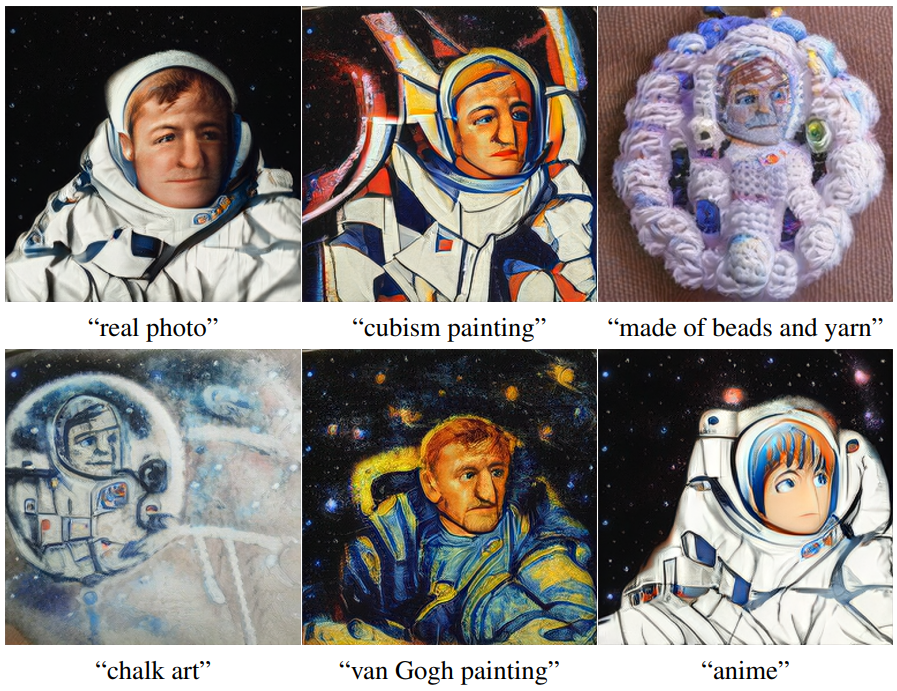

The following is an example of latent manipulation.

The following are samples generated by changing the X of the caption “astronaut, {X}” for a fixed random seed.

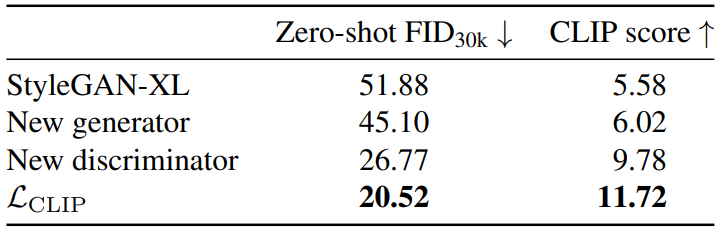

4. Architecture ablation

The following table shows the ablation for the architecture.

The redesign of the generator, the redesign of the discriminator, and the introduction of CLIP guidance can be seen to improve both the FID and CLIP scores, respectively.

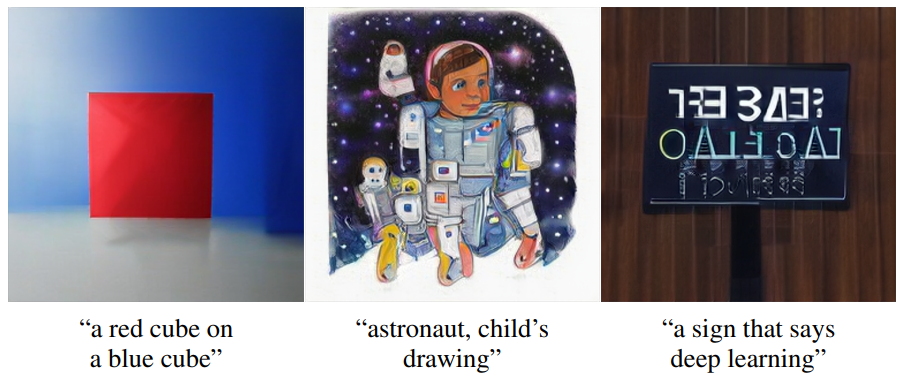

Limitations

Similar to DALL·E 2, which uses CLIP as its primary language model, StyleGAN-T struggles at times in terms of binding properties to objects and generating coherent text from images (see figure above). Using a larger language model can solve this problem at the expense of slower runtime.

Guidance through CLIP loss is essential for good text matching, but high guidance strength results in image artifacts. A possible solution is to retrain the CLIP on high-resolution data without aliasing or other image quality issues.

![[Paper review] Self-correcting LLM-controlled Diffusion Models](/assets/images/blog/post-5.jpg)